An interview with Boedi Widjaja, to accompany his solo presentation at I_S_L_A_N_D_S

“Imaginary homeland: kang ouw (一)” (17 January–21 February, 2018)

Boedi Widjaja was born in Solo City, Indonesia, and now lives and works in Singapore. Trained as an architect, he spent his young adulthood in graphic design, and turned to art in his thirties. His works often connect diverse conceptual references through his own lived experience of migration, culture and aesthetics; and investigate into concerns regarding diaspora, hybridity, travel and isolation. The artistic outcomes are processual and conceptually-charged, and embrace multiple mediums ranging from drawings to installations, sound and live art.

Growing up in Indonesia as a young child, severed from cultural roots, the artist looked to wuxia (武侠) — martial arts — novels and movies as a way to connect with his Chinese ethnicity. As a literary genre, wuxia established itself in Mainland China as a direct response to the May Fourth movement of 1919, calling for personal freedom and a break from Confucian values. Working around historical inconsistencies and genre-bending tropes, a more common structure in wuxia follows the protagonist’s progression from childhood to adulthood, much like a bildungsroman. And yet every so often, the lines between fiction and reality are blurred. You can’t help but notice the parallels here — the artist’s departure from Indonesia, and his subsequent migration to Singapore are very much inextricable from the political history of his homeland.

You mentioned that there was a shortage and/or lag in terms of the material that was coming into Indonesia. So in the 1980s, you could be watching wuxia films from the 1960s and 1970s, set in a timeless, pre-modern, mythical Chinese world. Growing up in Singapore during the 1990s also exposed you to a different set of Chinese culture. That’s a great deal of information (and time travel) to consolidate! How did you relate to it then, and now?

There was indeed a distinction between how I experienced Chinese culture in Indonesia and Singapore. In reference of a Chinese idiom, “to be away from one’s home in pursuit of scholarly honour or military duty” (书剑飘零) that speaks of being away from home, the former would be a sword and the latter, a book. I was born in Solo City (formerly Surakarta) during the New Order period. The period was known for its racialised socio-politics; Chinese culture was suppressed following the G30S event and the subsequent fall of Partai Komunis Indonesia (Communist Party of Indonesia) in 1965. Between the late 1970s and early 1980s however, Chinese cinema could still be found, and were accessible on VHS tapes in video rental shops (I later learnt they were pirated from Singapore). I was first introduced to wuxia films by my uncle who was a cinephile. He rented cartons of wuxia tapes and passed them to my family after he finished watching them. I didn’t understand Mandarin then but was quickly drawn to the action-packed world of wuxia — of fighting swordsmen who could levitate, their powerful sabres and earth-shattering inner energies. The experience was visceral — filled with violent actions, sound effects and dynamic movements.

When my sister and I first came to Singapore in 1984, we stayed with a Singaporean couple who happened to be members of the local Chinese theatre scene. In contrast to watching wuxia films back home, pop culture was generally frowned upon in their house. I was instead ‘strongly encouraged’ to read literary classics such as Dream of The Red Chamber (红楼梦), Water Margin (水浒传), Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义), and modern works such as Lu Xun’s The True Story of Ah Q (阿Q正传). I was then a kid learning Mandarin and must have found the books too difficult and serious to read! The couple also brought us to Chinese theatre performances, an art form that drew much from literary works. Chinese language — mostly in its written and oral form — defined my experience of the culture in this period of time.

Although the experiences were different, they both suggest an image of the Chinese diaspora’s imagining of their identity and feelings of nostalgia, as mediated through films and literature. It has been written about for example, that wuxia films made by studios in Hong Kong and Taiwan, were commercial products that catered to the overseas Chinese market and their longing for an imaginary China. In turn, my experience in Singapore was indirectly impacted by the raw emotions felt at the time by the locally educated Chinese population, post-merger of Nanyang University and University of Singapore.

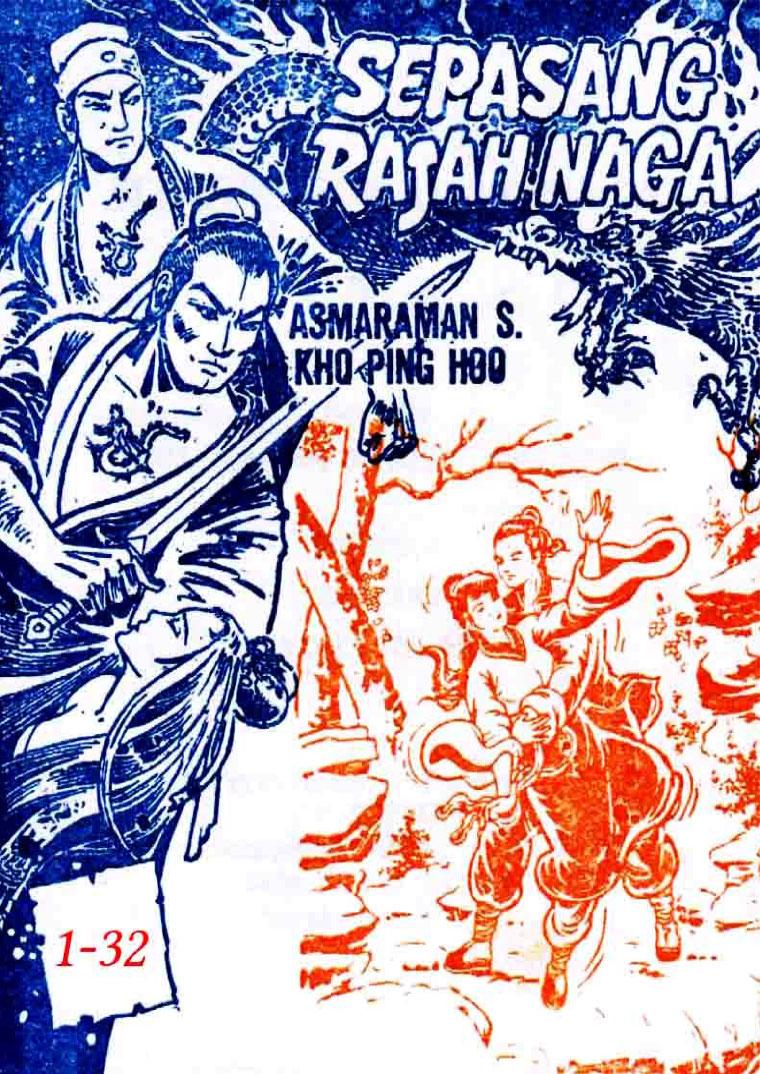

Whereas in previous iterations of of Imaginary homeland, you shift between drawing and photography, here you have turned your focus toward film and literature. Could you tell us more about the Indonesian author, Asmaran S. Kho Ping Hoo and his serialised novels, which serve as the inspiration behind this work?

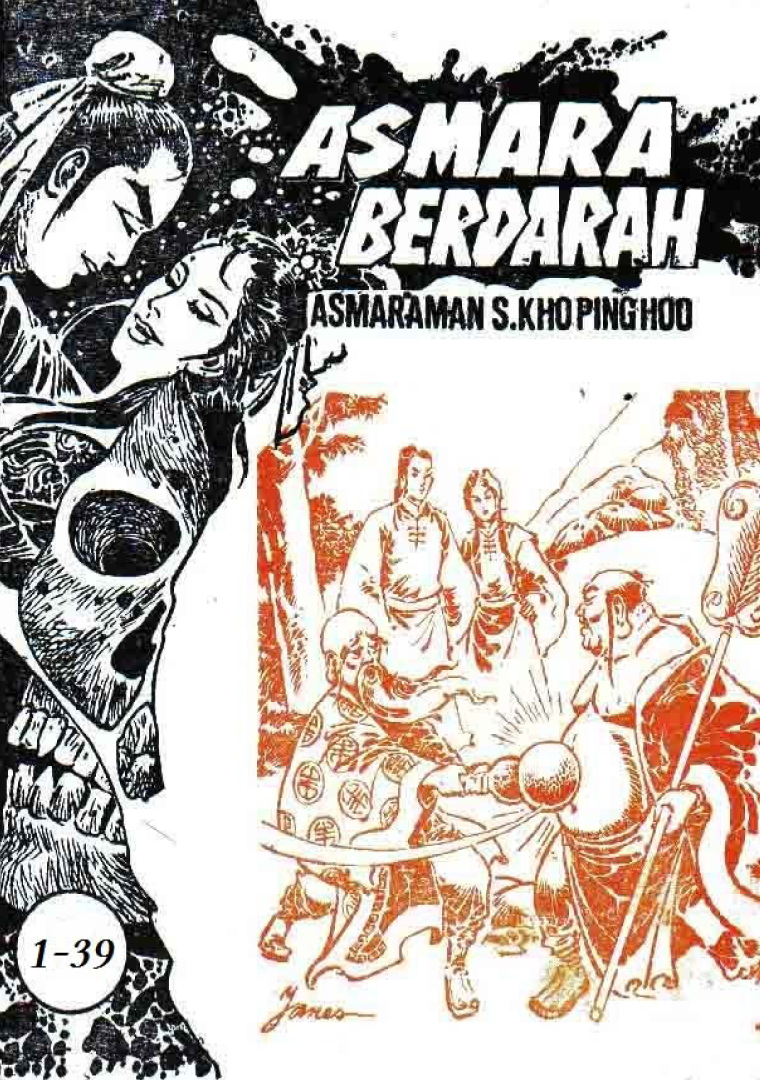

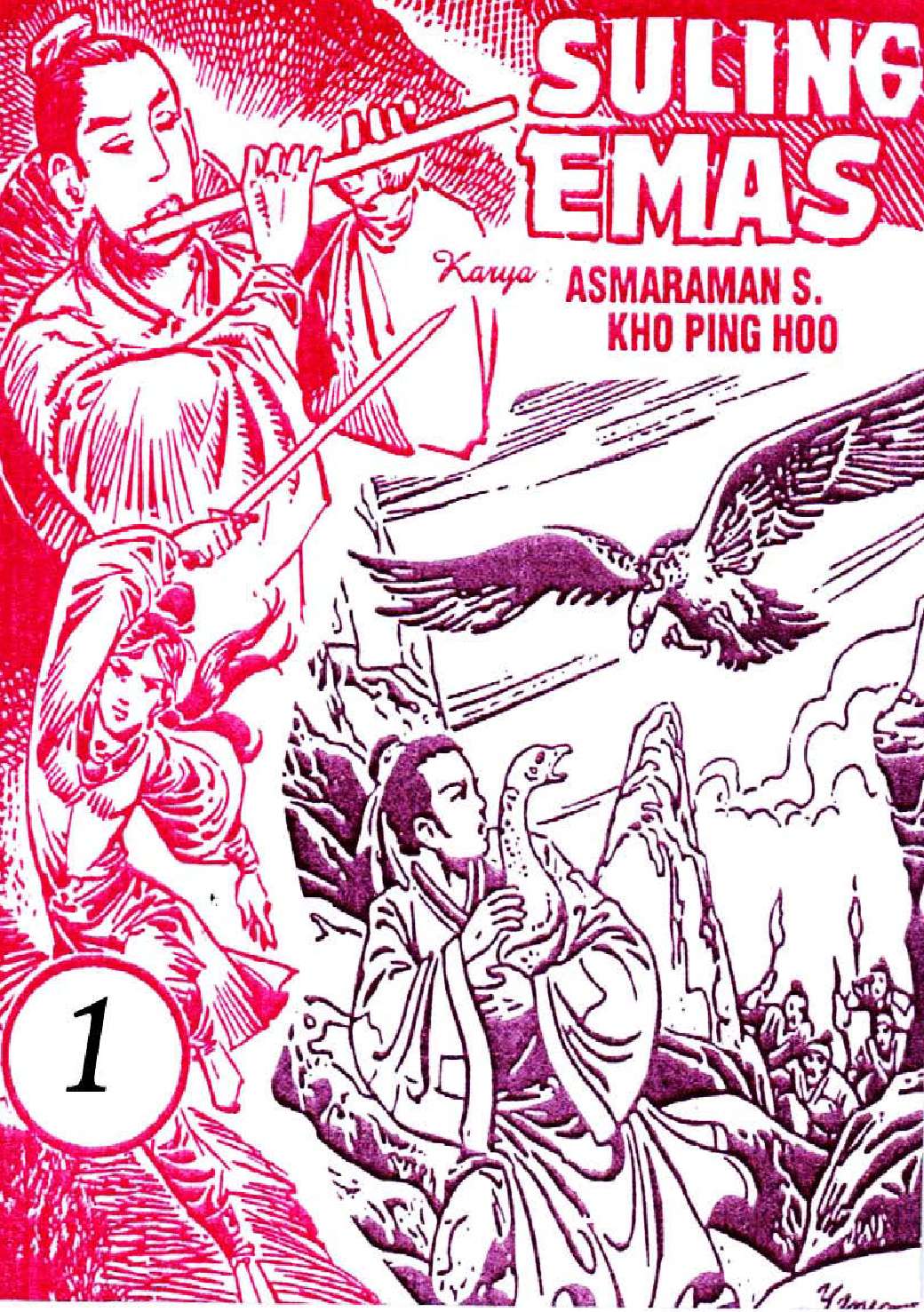

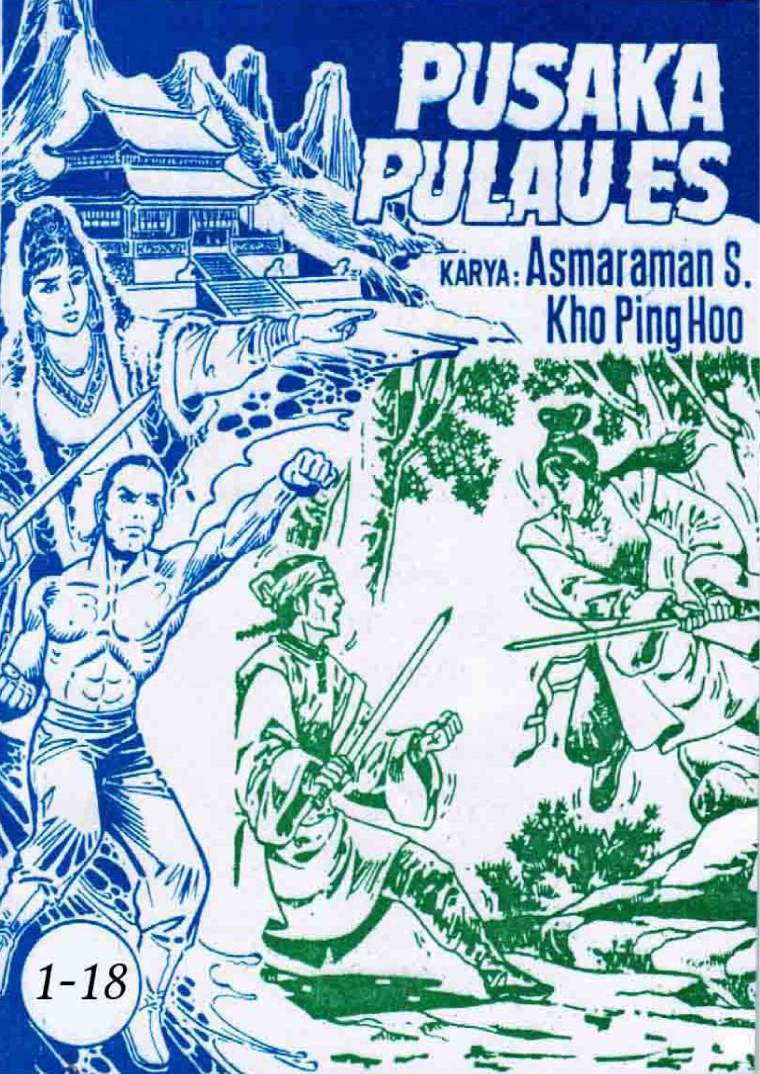

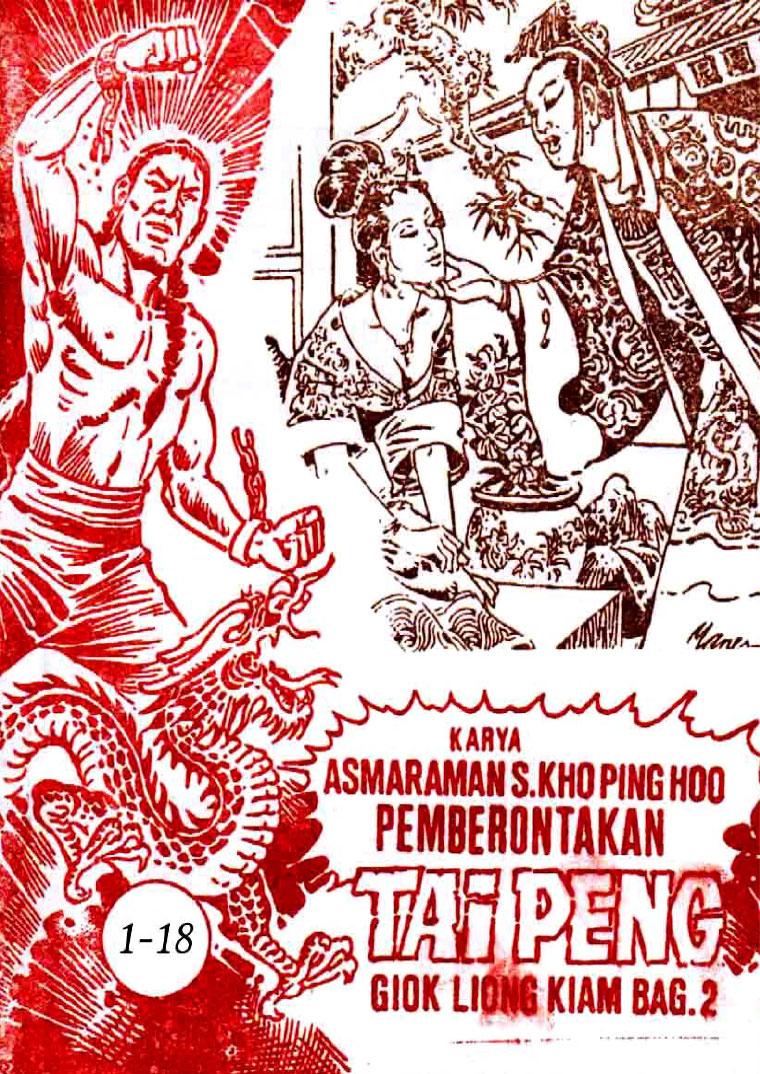

I got to know about Kho Ping Hoo a few years ago from my uncle (not the cinephile) when he bought me a few of KPH’s cersil series (cersil is an abbreviation of cerita silat in Bahasa Indonesia, which refers to martial arts novels). It was the books’ format that first caught my eye — each measured 10cm by 14cm, about 5mm thick, and printed on newsprint, they don’t look like your typical wuxia novel.

Later, i learnt that KPH was a popular (perhaps the most popular) cersil writer in Indonesia of his time. He was born in Sragen (which happened to be my mother’s hometown), and had taken on various jobs in different cities before establishing his reputation as a cersil writer in Tasikmalaya, a town near Jakarta, between 1958–1964. His life was marked by political chaos, enduring the Japanese invasion in 1942, the pro-independence battle of Surabaya in 1945, and in 1963, lost all he had in a racially motivated riot before moving to Solo City the year after.

KPH had started writing wuxia stories in order to attract readership for a literary magazine he founded during his time in Tasikmalaya. In contrast to some of his peers who also translated foreign wuxia stories, KPH’s oeuvre was mostly made up of original stories. He didn’t understand Mandarin and had supposedly relied on wuxia films (most likely subtitled in Bahasa Indonesia) as reference. An interesting time-based technique that he used was how a series would lead to another, with different characters who existed as sin tong (a transliteration of 神童 from Hokkien in Bahasa Indonesia) ‘growing up’ from childhood to adulthood across the different series. It has been speculated that his stories were partly autobiographical, as a way of describing his own wandering life amidst political chaos.

Your practice revolves around the act of excavating memories, marking origins, and exploring personal narratives. This act of ‘tracing’ is nowhere seen as directly as it is here in your work, Imaginary homeland: kang ouw (一). We’ve talked about how the Chinese term for ‘trace’ (描) could be implied in both writing and drawing. How do you apply this to the fiction and memories that you are attempting to place through this exercise?

Tracing an image by hand inevitably loses information of its reference but it also produces new modalities. Within a traced image lies the memory of its reference and the artist’s generative act. In a sense, the act of tracing embodies both imagination and recollection—the method suggesting a continuity of past and future, or of drawing a line across time. So far, the acts of tracing in my works are mostly of stones and with Imaginary homeland: kang ouw (一), tracing became a way to contemplate the wuxia films, which similar to the Chinese diaspora’s memory of their ancestral origins, are based on both historical references and cultural invention.

Boedi Widjaja, "Imaginary homeland, kang ouw (一)," process image. Image courtesy of the artist.

The film stills—in no particular order—are traced with carbon paper, scanned, and then Xeroxed. We don’t get to see the pages of the traditional bound book that holds these drawings. Why did you choose these particular modes of image reproduction?

Interestingly, the Chinese phrase for video (录影) comprises of two words that could mean ‘copy/record’ and ‘image/film’ respectively. What I did in Imaginary homeland: kang ouw (一) was to transpose (and transcribe), back-and-forth, my experience of wuxia in video and the printed book. In an abstract sense, the entire process could be seen as something that hovered between writing and filming. The tracing process was a tactile process that enabled me to viscerally connect with the flat, cinematic space of the stills.

By tracing only the images’ primary contours, the intent was to extract the action, movement and space of the film stills. In contrast, scanography and photocopy—flatbed photo techniques that responded to the flatness of the page—were used to place the book and the traces it contained, back into the floating world of images. While its pages were being scanned, the book was also at times physically shifted to introduce moments of disrupted space-time (akin to video edits) before the images were projected at a large scale using photocopy.

Boedi Widjaja, Imaginary homeland, kang ouw (一), photocopies of scanned drawings, 150 x 195 cm. Installation view at I_S_L_A_N_D_S, 17 January–21 February 2018. Image courtesy of the artist and I_S_L_A_N_D_S.

Bridging realms of space and time within a transitory passageway seems like an apt way to depict the subjective nature of memory. No longer contextually determined, the responsibility of assigning meaning to these images shifts from the original creators to the viewer, and circles back to you. What do you hope we will glean from this experience?

There indeed seems to be a number of space-time wormholes here. The exhibition site—a passageway between two of the oldest malls in an ever-changing city—naturally suggests a space to contemplate one’s memories; in this case, memories of a film/literary genre that acts as a quasi-time machine to a highly imagined past, for a community who is coming to terms with the liminality of their cultural identity. For an exhibition along a passageway that is about the fluid, mediated space between film and memory, I don’t wish to tell the audience which way to look. Perhaps, they can try to look to both directions, at the same time.

Thank you!

Boedi Widjaja — http://www.boediwidjaja.com