Describing a book as “life-changing” is a dramatic declaration. It suggests that the act of reading the book in question shifted the very foundations of one’s existence. However, the books I consider life-changing did not, in fact, alter the course of my life. Rather, I would say they gave my life a sense of form – by articulating ideas with an unprecedented depth, describing feelings with an intense accuracy, and imagining new worlds with an enthusiastic wonder. During the time spent immersed in a life-changing book, everything seems to make sense. The foundations of my existence do not shift, but they feel much stronger, steadier, now that some part of it – whether reality or dream – has been put into words.

Invisible Cities has never felt that way for me.

———

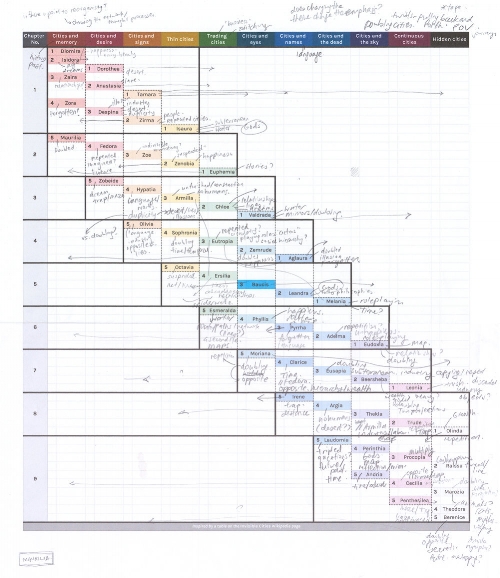

I am reading Invisible Cities for what must be the eleventh or twelfth time in my life. A majority of those times occurred in the last few weeks, in preparation for this project, as I mined the book for quotes and patterns and revelations. But the first time I read it must have been eight or nine years ago. My junior college art teacher had lent me an old copy of his – a grey-and-blue hardcover edition, its dust jacket long gone. I can’t remember exactly how he described the book, but I remember preparing for my mind to be blown.

It wasn’t. Instead, my mind was twisted, rearranged, befogged. I recognised the novel’s unusual brilliance, but overall the text felt opaque, despite moments of luminescence. Perhaps reading it even made me feel ignorant, and a little resentful of being made to feel ignorant – especially since the prose, though dense in parts, is not particularly difficult to understand. Each section felt as if it hinted at something larger or deeper than itself, and I wasn’t sure what that larger or deeper thing was.

Nevertheless, the book stayed with me, though for a long time I didn’t even own a copy. I thought the existing cover designs were too ugly or simple or unreflective of the text. Every bookstore I visited, I searched for Italo Calvino’s works, hoping to find a copy with a cover that felt right, and always failing. On the way, I picked up other books by Calvino, and in fact enjoyed a couple of them – such as If on a winter’s night a traveler – far more than Invisible Cities.