Words and thoughts by Berny Tan, regarding her solo presentation at I_S_L_A_N_D_S

“... the invisible reasons which make cities live...” (15 May–19 June, 2018)

Berny Tan (b. 1990) is a Singaporean artist, curator, writer and occasional designer. She previously worked as Assistant Curator for OH! Open House, a non-profit that explores Singapore’s cultural geography through art. Her art practice interweaves embroidery, drawing, installation, graphic design and writing – fundamentally exploring the tensions in her attempts to systematise intangible, emotional experiences.

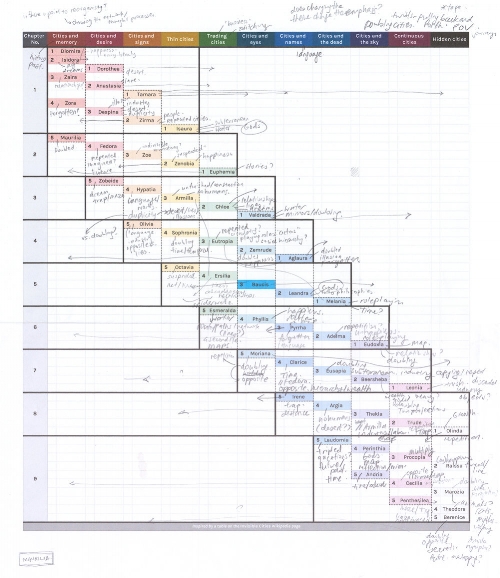

“... the invisible reasons which make cities live...” is Berny's exploration of the underlying structure in Italo Calvino's novel, Invisible Cities. The installation exudes a cool brevity and collectedness, something that can only be achieved after careful planning, and several rounds of trial and error. We invited Berny to share some (less structured) thoughts on this project, as well as the personal dynamics of reading and interpretation.

Berny Tan, “… the invisible reasons which make cities live…”, 2018, digital print on paper, pins, pearl cotton thread, yarn, stickers, dimensions variable. Installation view at I_S_L_A_N_D_S.

Describing a book as “life-changing” is a dramatic declaration. It suggests that the act of reading the book in question shifted the very foundations of one’s existence. However, the books I consider life-changing did not, in fact, alter the course of my life. Rather, I would say they gave my life a sense of form – by articulating ideas with an unprecedented depth, describing feelings with an intense accuracy, and imagining new worlds with an enthusiastic wonder. During the time spent immersed in a life-changing book, everything seems to make sense. The foundations of my existence do not shift, but they feel much stronger, steadier, now that some part of it – whether reality or dream – has been put into words.

Invisible Cities has never felt that way for me.

———

I am reading Invisible Cities for what must be the eleventh or twelfth time in my life. A majority of those times occurred in the last few weeks, in preparation for this project, as I mined the book for quotes and patterns and revelations. But the first time I read it must have been eight or nine years ago. My junior college art teacher had lent me an old copy of his – a grey-and-blue hardcover edition, its dust jacket long gone. I can’t remember exactly how he described the book, but I remember preparing for my mind to be blown.

It wasn’t. Instead, my mind was twisted, rearranged, befogged. I recognised the novel’s unusual brilliance, but overall the text felt opaque, despite moments of luminescence. Perhaps reading it even made me feel ignorant, and a little resentful of being made to feel ignorant – especially since the prose, though dense in parts, is not particularly difficult to understand. Each section felt as if it hinted at something larger or deeper than itself, and I wasn’t sure what that larger or deeper thing was.

Nevertheless, the book stayed with me, though for a long time I didn’t even own a copy. I thought the existing cover designs were too ugly or simple or unreflective of the text. Every bookstore I visited, I searched for Italo Calvino’s works, hoping to find a copy with a cover that felt right, and always failing. On the way, I picked up other books by Calvino, and in fact enjoyed a couple of them – such as If on a winter’s night a traveler – far more than Invisible Cities.

Cover art for Invisible Cities by Peter Mendelsund, created for a reissue of Calvino’s works from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

I finally bought my first copy of the novel last year, having found a cover that met my pointless aesthetic standards. I reread it, and though it felt more illuminating than my first encounter, that frustrating opacity lingered. Even now, after the eleventh or twelfth reading, after having read four academic papers about it (including a 200-page one about mathematics in the novel), I still find it confusing and uncomfortable, just as much as I find it beautiful and ingenious.

More than ever, I yearn to understand the book in its entirety. All these years I could never shake the feeling that I just needed to find the right method, or methods, to access it. Yes, reading Invisible Cities is uncomfortable, but it is a discomfort that hypnotises me, that I am intent on unpacking, even if there’s a whiff of impossibility about the task.

———

In the past six years of my art practice, I have completed a number of projects based on literature – more specifically, how the systems within a given text frame my experience as a reader, or how the systems I impose on the process of reading change my understanding of the text. For every single one of these projects, including this one on Invisible Cities, I have felt an underlying sense of futility. As much as I try to reflect on the text, as much as I try to find new ways of making connections with and within the text, there is always something fundamentally unknowable about it.

This is something with which I know I will always struggle – how to surrender to the unknowable, the uncertain, the undefined. Though Invisible Cities is intensely structured, though Calvino was obsessively deliberate in his language, the book possesses nebulous mysteries that I know I may never fully solve.

And so, here I am, filtering Invisible Cities through diagrams and notebooks and spreadsheets, seeking to comprehend something not fully comprehensible. Perhaps, years in the future, I will read this book for the thirty-eighth time and realise that I can finally call it a “life-changing” book, the way I’ve defined that term for myself at the very start of this short essay. Until then, I reserve a niche for it in my mind, a special place for this unresolvable thing.

(29 April 2018)